Remote Social TV

A research probe into emotions felt while watching a TV with a partner remotely

Basic project info

| My role | User Researcher, Data Scientist |

|---|---|

| Platform | Television, Video (platform agnostic) |

| Industry | TV broadcasting, On-demand video services |

| Period | Two weeks in Jan 2017 |

| Contract | Academic assignment |

Background

This project took place over a period of two weeks as part of the Affective Interaction module that I completed as part of the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) Master’s program at University College London. UCL Interaction Centre that delivers the HCI program is a world leading Centre of Excellence in Human-Computer Interaction.

The Challenge

My Role

This was an individual project – I conducted a literature review, proposed study design, conducted the research, proposed design recommendations and wrote up the report.

Target Audience

Primary

People using video-mediated communication technology in long-distance relationships

Secondary

People in different locations who want to stay in touch with their close ones by experiencing the same situations through video-mediated communication

Participants

A married couple was selected to participate in the study through an online screening questionnaire – the couple fulfilled the following research criteria:

- Had used a mainstream VMC in the past month

- Found watching TV/video programs with other people enjoyable

- Had not watched a video program with another person remotely before but would be interested in doing so

Process, methods & tools

This was a very small-scale study but I designed it in a way that could be easily scaled to many participants.

Literature review

I reviewed the literature on social TV, co-presence, video-mediated communication and how it relates to various emotions. A study that was closest to my interest was Macaranas et al.’s “Sharing Experiences over Video: Watching Video Programs Together at a Distance”.

Macaranas et al. conducted a study on how people use VMC to watch video programs together. They first ran a field study with 56 participants (29 male, 27 female), in which the participants engaged in watching a TV in pairs while being on Skype. Second study they conducted was a within-subject lab experiment with eight pairs of participants (6 male, 10 female) to explore the differences of watching TV together in three conditions: (1) being in the same room (local condition), (2) being in different rooms and using one device for VMC and a video (picture-in-picture (PIP) condition), (3) being in different rooms using different devices for VMC and a video (proxy condition).

The study provided valuable findings in a new field of research but focused primarily on usability issues and exploration of viewing settings; this presented an opportunity for expanding the study by examining the affective layer of the experience.

Pilot testing

Using two separate rooms, I conducted a pilot test with one of my acquaintances to assess the feasibility of PIP and proxy viewing settings. The proxy setting suffered from a strong audio cross-talk (echoes), which would make it impossible for the participants to communicate naturally. The PIP setting was therefore selected for the main experiment.

Several online services offering synchronised remote video watching were also evaluated during the pilot – rabb.it, netflixparty.com, showgoers.tv and letsgaze.com. Only letsgaze.com offered a picture-in-picture functionality and was therefore chosen for the experiment.

Experiment

Participants were situated in two separate flats in London. Sitting on a sofa in a living room, they were briefed and asked to sign an informed consent. Then, they were given time to select a video they would both want to watch – they selected one episode of The Simpsons.

Next, they spent approximately 20 minutes watching, being each alone in the room. The participants were briefed to behave naturally and told they would not be tested on the content of the video.

Right after the experience, I carried out a semi-structured interview with each participant in turn.

Semi-structured interviews

In order to understand affective states experienced during the experiment, several interview techniques and frameworks were embedded into the interview process and questions. Mauss and Robinson in their review article on measures of emotion suggest that self-reports of emotion are generally more valid when applied to the currently experienced emotions or directly after an event. Interviews were therefore conducted right after the experiment. The interview structure followed the Spatio-temporal thread of the McCarthy and Wright’s Technology as experience framework – the participants were guided to relive the experience from the beginning to the end. This was combined with Petitmengin’s interview method which aims to elicit precise descriptions of participants’ subjective experiences. Following this method, participants’ attention was first stabilised by setting expectations about the length of the interview and its focus (the interaction between the participants, not the video content). Then, they were guided to reconstruct and describe the interactions between them during the experiment. Building on the related research of social presence and ambient social TV, measures of social presence and co-presence from the Networked Minds Social Presence Inventory which normally serve as questionnaire scales, were adapted and incorporated into the interview to explore the sense of co-presence between participants. Lastly, at the end of the interview, the participants were asked to reflect on the experience as a whole following Norman’s three-tier design framework which includes visceral, behavioural and reflective levels. Norman argues that only the reflective level requires conscious interpretation. It is, therefore, suitable to be explored in an interview.

Microsoft Emotion API – Facial expression analysis

I used the MS Emotion API to analyse facial expressions of the participants captured during the experiment. The API returns eight basic emotion values. Although sounding promising the results were disappointing. When manually comparing the videos, and detected emotions, there were obvious glitches (e.g. returning surprise when a participant touched her mouth). The data overall did not correlate well with manual assessment and is not therefore reported. Although a valuable lesson was learnt – the technology is still not ready to supplement research.

Tools I used

- Two laptops running letsgaze.com

- NVivo 11 (for interview transcripts and thematic analysis)

- Microsoft Emotion API

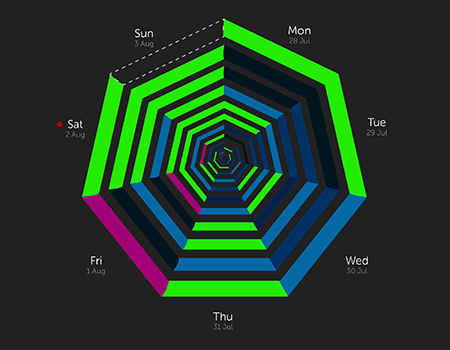

- Exploratory.io (An R-based data science tool to analyse emotions)

Identified Affective States

Six overarching themes

The participants did not find the experience very enjoyable, which reflects in the six overarching themes identified:

- Privacy intrusion

- Situational objective self-awareness

- Boredom

- Divided attention

- Obligation to interact

- Expecting emotion reciprocity

Each theme was examined and affective states were extrapolated based on literature review findings, participants‘ self-report and analysis of the videos from the experiment. Identified affective states were confirmed with the participants in a follow-up session in which a video of the experiment was re-played.

Affective states taxonomies

Before assigning specific names to identified affective states, I reviewed three seminal affective state taxonomies:

- Plutchik’s three-dimensional model

- Rusell and Barrett’s Core affect model

- Ortony, Clore and Foss’s Affective Lexicon

Identified affective states

Based on all of the above, I identified the following affective states:

- Alertness

- Anxiety

- Boredom

- Disappointment

- Discouragement

- Encouragement (negative valence)

- Overwhelmedness

- Vigilance

If you are interested in a detailed description of each state, please have a look at the study report below.

Design recommendations

I picked two significant affective states that I identified, explored literature and suggested how the current problems with the technology could be overcome.

Situational social anxiety

Design space 1 – Reducing anxiety using Tangible user interfaces

While watching a synchronised video stream on a TV or other device, users could use an external device that could use light intensity and colour as means to communicate presence to each other.

Another option to explore could be a tangible device that would warm up to communicate presence, this could further enhance a sense of intimacy that long-distance relationships lack.

Design space 2 – Reducing anxiety using Graphical user interfaces

Staying within a more traditional web and app design, possible directions worth exploring include adding a coloured strip or dot to ambiently represent the other user, replacing the video chat. Presence could be communicated by changing colour hue and intensity.

If a device had a touch display, a simple touch on the strip/dot could communicate the presence and closeness to the other user.

Boredom

A set of activities related to the program watched could be available to the user should they get bored. These could have for example a form of interesting facts about the program, that could be displayed as snap messages on the screen.

Since reading takes more attentional resources than listening, the service could provide an option to switch languages and displaying subtitles, so that users could independently watch the program in different languages.

This may allow a person who gets bored to practise a second language, which may be more stimulating.

Study report

If you are interested in learning more about the project, have a look at the report (unpublished). I describe the identified affective states in more detail and I provide more background to the above design recommendations.